Win Production Functions for AFL Teams - 1897 to 2010

/A Proposition Bet on the Game Margin

/We've not had a proposition bet for a while, so here's the bet and a spiel to go with it:

"If the margin at quarter time is a multiple of 6 points I'll pay you $5; if it's not, you pay me a $1. If the two teams are level at quarter-time it's a wash and neither of us pay the other anything.

Now quarter-time margins are unpredictable, so the probability of the margin being a multiple of 6 is 1-in-6, so my offering you odds of 5/1 makes it a fair bet, right? Actually, since goals are worth six points, you've probably got the better of the deal, since you'll collect if both teams kick the same number of behinds in the quarter.

Deal?"

At first glance this bet might look reasonable, but it isn't. I'll take you through the mechanics of why, and suggest a few even more lucrative variations.

Firstly, taking out the drawn quarter scenario is important. Since zero is divisible by 6 - actually, it's divisible by everything but itself - this result would otherwise be a loser for the bet proposer. Historically, about 2.4% of games have been locked up at the end of the 1st quarter, so you want those games off the table.

You could take the high moral ground on removing the zero case too, because your probability argument implicitly assumes that you're ignoring zeroes. If you're claiming that the chances of a randomly selected number being divisible by 6 is 1-in-6 then it's as if you're saying something like the following:

"Consider all the possible margins of 12 goals or less at quarter time. Now twelve of those margins - 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, 36, 42, 48, 54, 60, 66 and 72 - are divisible by 6, and the other 60, excluding 0, are not. So the chances of the margin being divisible by 6 are 12-in-72 or 1-in-6."

In running that line, though, I'm making two more implicit assumptions, one fairly obvious and the other more subtle.

The obvious assumption I'm making is that every margin is equally likely. Demonstrably, it's not. Smaller margins are almost universally more frequent than larger margins. Because of this, the proportion of games with margins of 1 to 5 points is more than 5 times larger than the proportion of games with margins of exactly 6 points, the proportion of games with margins of 7 to 11 points is more than 5 times larger than the proportion of games with margins of exactly 12 points, and so on. It's this factor that, primarily, makes the bet profitable.

The tendency for higher margins to be less frequent is strong, but it's not inviolate. For example, historically more games have had a 5-point margin at quarter time than a 4-point margin, and more have had an 11-point margin than a 10-point margin. Nonetheless, overall, the declining tendency has been strong enough for the proposition bet to be profitable as I've described it.

Here is a chart of the frequency distribution of margins at the end of the 1st quarter.

The far-less obvious assumption in my earlier explanation of the fairness of the bet is that the bet proposer will have exactly five-sixths of the margins in his or her favour; he or she will almost certainly have more than this, albeit only slightly more.

This is because there'll be a highest margin and that highest margin is more likely not to be divisible by 6 than it is to be divisible by 6. The simple reason for this is, as we've already noted, that only one-sixth of all numbers are divisible by six.

So if, for example, the highest margin witnessed at quarter-time is 71 points (which, actually, it is), then the bet proposer has 60 margins in his or her favour and the bet acceptor has only 11. That's 5 more margins in the proposer's favour than the 5/1 odds require, even if every margin was equally likely.

The only way for the ratio of margins in favour of the proposer to those in favour of the acceptor to be exactly 5-to-1 would be for the highest margin to be an exact multiple of 6. In all other cases, the bet proposer has an additional edge (though to be fair it's a very, very small one - about 0.02%).

So why did I choose to settle the bet at the end of the 1st quarter and not instead, say, at the end of the game?

Well, as a game progresses the average margin tends to increase and that reduces the steepness of the decline in frequency with increasing margin size.

Here's the frequency distribution of margins as at game's end.

(As well as the shallower decline in frequencies, note how much less prominent the 1-point game is in this chart compared to the previous one. Games that are 1-point affairs are good for the bet proposer.)

The slower rate of decline when using 4th-quarter rather than 1st-quarter margins makes the wager more susceptible to transient stochastic fluctuations - or what most normal people would call 'bad luck' - so much so that the wager would have been unprofitable in just over 30% of the 114 seasons from 1897 to 2010, including a horror run of 8 losing seasons in 13 starting in 1956 and ending in 1968.

Across all 114 seasons taken as a whole though it would also have been profitable. If you take my proposition bet as originally stated and assume that you'd found a well-funded, if a little slow and by now aged, footballing friend who'd taken this bet since the first game in the first round of 1897, you'd have made about 12c per game from him or her on average. You'd have paid out the $5 about 14.7% of the time and collected the $1 the other 85.3% of the time.

Alternatively, if you'd made the same wager but on the basis of the final margin, and not the margin at quarter-time, then you'd have made only 7.7c per game, having paid out 15.4% of the time and collected the other 84.6% of the time.

One way that you could increase your rate of return, whether you choose the 1st- or 4th-quarter margin as the basis for determining the winner, would be to choose a divisor higher than 6. So, for example, you could offer to pay $9 if the margin at quarter-time was divisible by 10 and collect $1 if it wasn't. By choosing a higher divisor you virtually ensure that there'll be sufficient decline in the frequencies that your wager will be profitable.

In this last table I've provided the empirical data for the profitability of every divisor between 2 and 20. For a divisor of N the bet is that you'll pay $N-1 if the margin is divisible by N and you'll receive $1 if it isn't. The left column shows the profit if you'd settled the bet at quarter-time, and the right column if you'd settled it all full-time.

As the divisor gets larger, the proposer benefits from the near-certainty that the frequency of an exactly-divisible margin will be smaller than what's required for profitability; he or she also benefits more from the "extra margins" effect since there are likely to be more of them and, for the situation where the bet is being settled at quarter-time, these extra margins are more likely to include a significant number of games.

Consider, for example, the bet for a divisor of 20. For that wager, even if the proportion of games ending the quarter with margins of 20, 40 or 60 points is about one-twentieth the total proportion ending with a margin of 60 points or less, the bet proposer has all the margins from 61 to 71 points in his or her favour. That, as it turns out, is about another 11 games, or almost 0.1%. Every little bit helps.

Which Teams Are Most Likely to Make Next Year's Finals?

/I had a little time on a flight back to Sydney from Melbourne last Friday night to contemplate life's abiding truths. So naturally I wondered: how likely is it that a team finishing in ladder position X at the end of one season makes the finals in the subsequent season?

Here's the result for seasons 2000 to 2010, during which the AFL has always had a final 8:

When you bear in mind that half of the 16 teams have played finals in each season since 2000 this table is pretty eye-opening. It suggests that the only teams that can legitimately feel themselves to be better-than-random chances for a finals berth in the subsequent year are those that have finished in the top 4 ladder positions in the immediately preceding season. Historically, top 4 teams have made the 8 in the next year about 70% of the time - 100% of the time in the case of the team that takes the minor premiership.

In comparison, teams finishing 5th through 14th have, empirically, had roughly a 50% chance of making the finals in the subsequent year (actually, a tick under this, which makes them all slightly less than random chances to make the 8).

Teams occupying 15th and 16th have had very remote chances of playing finals in the subsequent season. Only one team from those positions - Collingwood, who finished 15th in 2005 and played finals in 2006 - has made the subsequent year's top 8.

Of course, next year we have another team, so that's even worse news for those teams that finished out of the top 4 this year.

Coast-to-Coast Blowouts: Who's Responsible and When Do They Strike?

/Previously, I created a Game Typology for home-and-away fixtures and then went on to use that typology to characterise whole seasons and eras.

In this blog we'll use that typology to investigate the winning and losing tendencies of individual teams and to consider how the mix of different game types varies as the home-and-away season progresses.

First, let's look at the game type profile of each team's victories and losses in season 2010.

Five teams made a habit of recording Coast-to-Coast Comfortably victories this season - Carlton, Collingwood, Geelong, Sydney and the Western Bulldogs - all of them finalists, and all of them winning in this fashion at least 5 times during the season.

Two other finalists, Hawthorn and the Saints, were masters of the Coast-to-Coast Nail-Biter. They, along with Port Adelaide, registered four or more of this type of win.

Of the six other game types there were only two that any single team recorded on 4 occasions. The Roos managed four Quarter 2 Press Light victories, and Geelong had four wins categorised as Quarter 3 Press victories.

Looking next at loss typology, we find six teams specialising in Coast-to-Coast Comfortably losses. One of them is Carlton, who also appeared on the list of teams specialising in wins of this variety, reinforcing the point that I made in an earlier blog about the Blues' fate often being determined in 2010 by their 1st quarter performance.

The other teams on the list of frequent Coast-to-Coast Comfortably losers are, unsurprisingly, those from positions 13 through 16 on the final ladder, and the Roos. They finished 9th on the ladder but recorded a paltry 87.4 percentage, this the logical consequence of all those Coast-to-Coast Comfortably losses.

Collingwood and Hawthorn each managed four losses labelled Coast-to-Coast Nail-Biters, and West Coast lost four encounters that were Quarter 2 Press Lights, and four more that were 2nd-Half Revivals where they weren't doing the reviving.

With only 22 games to consider for each team it's hard to get much of a read on general tendencies. So let's increase the sample by an order of magnitude and go back over the previous 10 seasons.

Adelaide's wins have come disproportionately often from presses in the 1st or 2nd quarters and relatively rarely from 2nd-Half Revivals or Coast-to-Coast results. They've had more than their expected share of losses of type Q2 Press Light, but less than their share of Q1 Press and Coast-to-Coast losses. In particular, they've suffered few Coast-to-Coast Blowout losses.

Brisbane have recorded an excess of Coast-to-Coast Comfortably and Blowout victories and less Q1 Press, Q3 Press and Coast-to-Coast Nail-Biters than might be expected. No game type has featured disproportionately more often amongst their losses, but they have had relatively few Q2 Press and Q3 Press losses.

Carlton has specialised in the Q2 Press victory type and has, relatively speaking, shunned Q3 Press and Coast-to-Coast Blowout victories. Their losses also include a disportionately high number of Q2 Press losses, which suggests that, over the broader time horizon of a decade, Carlton's fate has been more about how they've performed in the 2nd term. Carlton have also suffered a disproportionately high share of Coast-to-Coast Blowouts - which is I suppose what a Q2 Press loss might become if it gets ugly - yet have racked up fewer than the expected number of Coast-to-Coast Nail-Biters and Coast-to-Coast Comfortablys. If you're going to lose Coast-to-Coast, might as well make it a big one.

Collingwood's victories have been disproportionately often 2nd-Half Revivals or Coast-to-Coast Blowouts and not Q1 Presses or Coast-to-Coast Nail-Biters. Their pattern of losses has been partly a mirror image of their pattern of wins, with a preponderance of Q1 Presses and Coast-to-Coast Nail-Biters and a scarcity of 2nd-Half Revivals. They've also, however, had few losses that were Q2 or Q3 Presses or that were Coast-to-Coast Comfortablys.

Wins for Essendon have been Q1 Presses or Coast-to-Coast Nail-Biters unexpectedly often, but have been Q2 Press Lights or 2nd-Half Revivals significantly less often than for the average team. The only game type overrepresented amongst their losses has been the Coast-to-Coast Comfortably type, while Coast-to-Coast Blowouts, Q1 Presses and, especially, Q2 Presses have been signficantly underrepresented.

Fremantle's had a penchant for leaving their runs late. Amongst their victories, Q3 Presses and 2nd-Half Revivals occur more often than for the average team, while Coast-to-Coast Blowouts are relatively rare. Their losses also have a disproportionately high showing of 2nd-Half Revivals and an underrepresentation of Coast-to-Coast Blowouts and Coast-to-Coast Nail-Biters. It's fair to say that Freo don't do Coast-to-Coast results.

Geelong have tended to either dominate throughout a game or to leave their surge until later. Their victories are disproportionately of the Coast-to-Coast Blowout and Q3 Press varieties and are less likely to be Q2 Presses (Regular or Light) or 2nd-Half Revivals. Losses have been Q2 Press Lights more often than expected, and Q1 Presses, Q3 Presses or Coast-to-Coast Nail-Biters less often than expected.

Hawthorn have won with Q2 Press Lights disproportionately often, but have recorded 2nd-Half Revivals relatively infrequently and Q2 Presses very infrequently. Q2 Press Lights are also overrepresented amongst their losses, while Q2 Presses and Coast-to-Coast Nail-Biters appear less often than would be expected.

The Roos specialise in Coast-to-Coast Nail-Biter and Q2 Press Light victories and tend to avoid Q2 and Q3 Presses, as well as Coast-to-Coast Comfortably and Blowout victories. Losses have come disproportionately from the Q3 Press bucket and relatively rarely from the Q2 Press (Regular or Light) categories. The Roos generally make their supporters wait until late in the game to find out how it's going to end.

Melbourne heavily favour the Q2 Press Light style of victory and have tended to avoid any of the Coast-to-Coast varieties, especially the Blowout variant. They have, however, suffered more than their share of Coast-to-Coast Comfortably losses, but less than their share of Coast-to-Coast Blowout and Q2 Press Light losses.

Port Adelaide's pattern of victories has been a bit like Geelong's. They too have won disproportionately often via Q3 Presses or Coast-to-Coast Blowouts and their wins have been underrepresented in the Q2 Press Light category. They've also been particularly prone to Q2 and Q3 Press losses, but not to Q1 Presses or 2nd-Half Revivals.

Richmond wins have been disproportionately 2nd-Half Revivals or Coast-to-Coast Nail-Biters, and rarely Q1 or Q3 Presses. Their losses have been Coast-to-Coast Blowouts disproportionately often, but Coast-to-Coast Nail-Biters and Q2 Press Lights relatively less often than expected.

St Kilda have been masters of the foot-to-the-floor style of victory. They're overrepresented amongst Q1 and Q2 Presses, as well as Coast-to-Coast Blowouts, and underrepresented amongst Q3 Presses and Coast-to-Coast Comfortablys. Their losses include more Coast-to-Coast Nail-Biters than the average team, and fewer Q1 and Q3 Presses, and 2nd-Half Revivals.

Sydney's loss profile almost mirrors the average team's with the sole exception being a relative abundance of Q3 Presses. Their profile of losses, however, differs significantly from the average and shows an excess of Q1 Presses, 2nd-Half Revivals and Coast-to-Coast Nail-Biters, a relative scarcity of Q3 Presses and Coast-to-Coast Comfortablys, and a virtual absence of Coast-to-Coast Blowouts.

West Coast victories have come disproportionately as Q2 Press Lights and have rarely been of any other of the Press varieties. In particular, Q2 Presses have been relatively rare. Their losses have all too often been Coast-to-Coast blowouts or Q2 Presses, and have come as Coast-to-Coast Nail-Biters relatively infrequently.

The Western Bulldogs have won with Coast-to-Coast Comfortablys far more often than the average team, and with the other two varieties of Coast-to-Coast victories far less often. Their profile of losses mirrors that of the average team excepting that Q1 Presses are somewhat underrepresented.

We move now from associating teams with various game types to associating rounds of the season with various game types.

You might wonder, as I did, whether different parts of the season tend to produce a greater or lesser proportion of games of particular types. Do we, for example, see more Coast-to-Coast Blowouts early in the season when teams are still establishing routines and disciplines, or later on in the season when teams with no chance meet teams vying for preferred finals berths?

For this chart, I've divided the seasons from 2001 to 2010 into rough quadrants, each spanning 5 or 6 rounds.

The Coast-to-Coast Comfortably game type occurs most often in the early rounds of the season, then falls away a little through the next two quadrants before spiking a little in the run up to the finals.

The pattern for the Coast-to-Coast Nail-Biter game type is almost the exact opposite. It's relatively rare early in the season and becomes more prevalent as the season progresses through its middle stages, before tapering off in the final quadrant.

Coast-to-Coast Blowouts occur relatively infrequently during the first half of the season, but then blossom, like weeds, in the second half, especially during the last 5 rounds when they reach near-plague proportions.

Quarter 1 and Quarter 2 Presses occur with similar frequencies across the season, though they both show up slightly more often as the season progresses. Quarter 2 Press Lights, however, predominate in the first 5 rounds of the season and then decline in frequency across rounds 6 to 16 before tapering dramatically in the season's final quadrant.

Quarter 3 Presses occur least often in the early rounds, show a mild spike in Rounds 6 to 11, and then taper off in frequency across the remainder of the season. 2nd-Half Revivals show a broadly similar pattern.

2010: Just How Different Was It?

/Last season I looked at Grand Final Typology. In this blog I'll start by presenting a similar typology for home-and-away games.

In creating the typology I used the same clustering technique that I used for Grand Finals - what's called Partitioning Around Medoids, or PAM - and I used similar data. Each of the 13,144 home-and-away season games was characterised by four numbers: the winning team's lead at quarter time, at half-time, at three-quarter time, and at full time.

With these four numbers we can calculate a measure of distance between any pair of games and then use the matrix of all these distances to form clusters or types of games.

After a lot of toing, froing, re-toing anf re-froing, I settled on a typology of 8 game types:

Typically, in the Quarter 1 Press game type, the eventual winning team "presses" in the first term and leads by about 4 goals at quarter-time. At each subsequent change and at the final siren, the winning team typically leads by a little less than the margin it established at quarter-time. Generally the final margin is about about 3 goals. This game type occurs about 8% of the time.

In a Quarter 2 Press game type the press is deferred, and the eventual winning team typically trails by a little over a goal at quarter-time but surges in the second term to lead by four-and-a-half goals at the main break. They then cruise in the third term and extend their lead by a little in the fourth and ultimately win quite comfortably, by about six and a half goals. About 7% of all home-and-away games are of this type.

The Quarter 2 Press Light game type is similar to a Quarter 2 Press game type, but the surge in the second term is not as great, so the eventual winning team leads at half-time by only about 2 goals. In the second half of a Quarter 2 Press Light game the winning team provides no assurances for its supporters and continues to lead narrowly at three-quarter time and at the final siren. This is one of the two most common game types, and describes almost 1 in 5 contests.

Quarter 3 Press games are broadly similar to Quarter 1 Press games up until half-time, though the eventual winning team typically has a smaller lead at that point in a Quarter 3 Press game type. The surge comes in the third term where the winners typically stretch their advantage to around 7 goals and then preserve this margin until the final siren. Games of this type comprise about 10% of home-and-away fixtures.

2nd-Half Revival games are particularly closely fought in the first two terms with the game's eventual losers typically having slightly the better of it. The eventual winning team typically trails by less than a goal at quarter-time and at half-time before establishing about a 3-goal lead at the final change. This lead is then preserved until the final siren. This game type occurs about 13% of the time.

A Coast-to-Coast Nail-Biter is the game type that's the most fun to watch - provided it doesn't involve your team, especially if your team's on the losing end of one of these contests. In this game type the same team typically leads at every change, but by less than a goal to a goal and a half. Across history, this game type has made up about one game in six.

The Coast-to-Coast Comfortably game type is fun to watch as a supporter when it's your team generating the comfort. Teams that win these games typically lead by about two and a half goals at quarter-time, four and a half goals at half-time, six goals at three-quarter time, and seven and a half goals at the final siren. This is another common game type - expect to see it about 1 game in 5 (more often if you're a Geelong or a West Coast fan, though with vastly differing levels of pleasure depending on which of these two you support).

Coast-to-Coast Blowouts are hard to love and not much fun to watch for any but the most partial observer. They start in the manner of a Coast-to-Coast Comfortably game, with the eventual winner leading by about 2 goals at quarter time. This lead is extended to six and a half goals by half-time - at which point the word "contest" no longer applies - and then further extended in each of the remaining quarters. The final margin in a game of this type is typically around 14 goals and it is the least common of all game types. Throughout history, about one contest in 14 has been spoiled by being of this type.

Unfortunately, in more recent history the spoilage rate has been higher, as you can see in the following chart (for the purposes of which I've grouped the history of the AFL into eras each of 12 seasons, excepting the most recent era, which contains only 6 seasons. I've also shown the profile of results by game type for season 2010 alone).

The pies in the bottom-most row show the progressive growth in the Coast-to-Coast Blowout commencing around the 1969-1980 era and reaching its apex in the 1981-1992 era where it described about 12% of games.

In the two most-recent eras we've seen a smaller proportion of Coast-to-Coast Blowouts, but they've still occurred at historically high rates of about 8-10%.

We've also witnessed a proliferation of Coast-to-Coast Comfortably and Coast-to-Coast Nail-Biter games in this same period, not least of which in the current season where these game type descriptions attached to about 27% and 18% of contests respectively.

In total, almost 50% of the games this season were Coast-to-Coast contests - that's about 8 percentage points higher than the historical average.

Of the five non Coast-to-Coast game types, three - Quarter 2 Press, Quarter 3 Press and 2nd-half Revival - occurred at about their historical rates this season, while Quarter 1 Press and Quarter 2 Press Light game typesboth occurred at about 75-80% of their historical rates.

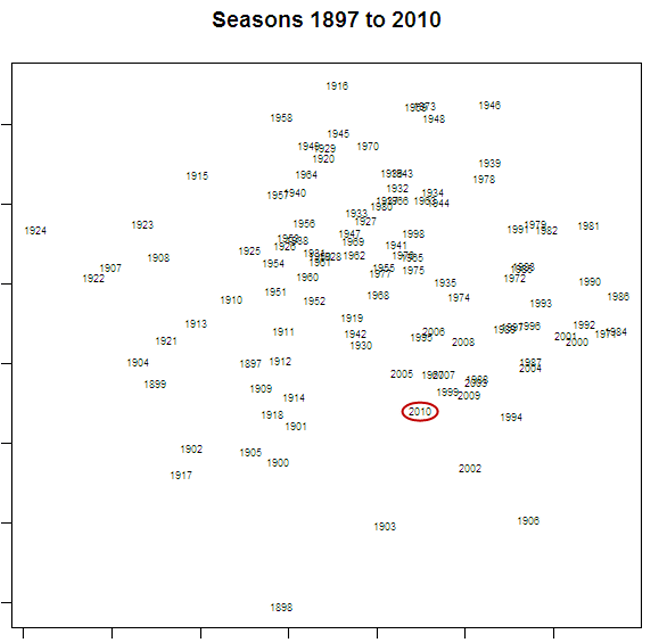

The proportion of games of each type in a season can be thought of as a signature of that season. being numeric, they provide a ready basis on which to measure how much one season is more or less like another. In fact, using a technique called principal components analysis we can use each season's signature to plot that season in two-dimensional space (using the first two principal components).

Here's what we get:

I've circled the point labelled "2010", which represents the current season. The further away is the label for another season, the more different is that season's profile of game types in comparison to 2010's profile.

So, for example, 2009, 1999 and 2005 are all seasons that were quite similar to 2010, and 1924, 1916 and 1958 are all seasons that were quite different. The table below provides the profile for each of the seasons just listed; you can judge the similarity for yourself.

Signatures can also be created for eras and these signatures used to represent the profile of game results from each era. If you do this using the eras as I've defined them, you get the chart shown below.

One way to interpret this chart is that there have been 3 super-eras in VFL/AFL history, the first spanning the seasons from 1897 to 1920, the second from 1921-1980, and the third from 1981-2010. In this latter era we seem to be returning to the profiles of the earliest eras, which was a time when 50% or more of all results were Coast-to-Coast game types.

Season 2010: An Assessment of Competitiveness

/For many, the allure of sport lies in its uncertainty. It's this instinct, surely, that motivated the creation of the annual player drafts and salary caps - the desire to ensure that teams don't become unbeatable, that "either team can win on the day".

Objective measures of the competitiveness of AFL can be made at any of three levels: teams' competition wins and losses, the outcome of a game, or the in-game trading of the lead.

With just a little pondering, I came up with the following measures of competitiveness at the three levels; I'm sure there are more.

We've looked at most - maybe all - of the Competition and Game level measures I've listed here in blogs or newsletters of previous seasons. I'll leave any revisiting of these measures for season 2010 as a topic for a future blog.

The in-game measures, though, are ones we've not explicitly explored, though I think I have commented on at least one occasion this year about the surprisingly high proportion of winning teams that have won 1st quarters and the low proportion of teams that have rallied to win after trailing at the final change.

As ever, history provides some context for my comments.

The red line in this chart records the season-by-season proportion of games in which the same team has led at every change. You can see that there's been a general rise in the proportion of such games from about 50% in the late seventies to the 61% we saw this year.

In recent history there have only been two seasons where the proportion of games led by the same team at every change has been higher: in 1995, when it was almost 64%, and in 1985 when it was a little over 62%. Before that you need to go back to 1925 to find a proportion that's higher than what we've seen in 2010.

The green, purple and blue lines track the proportion of games for which there were one, two, and the maximum possible three lead changes respectively. It's also interesting to note how the lead-change-at-every-change contest type has progressively disappeared into virtual non-existence over the last 50 seasons. This year we saw only three such contests, one of them (Fremantle v Geelong) in Round 3, and then no more until a pair of them (Fremantle v Geelong and Brisbane v Adelaide) in Round 20.

So we're getting fewer lead changes in games. When, exactly, are these lead changes not happening?

Pretty much everywhere, it seems, but especially between the ends of quarters 1 and 2.

The top line shows the proportion of games in which the team leading at half time differs from the team leading at quarter time (a statistic that, as for all the others in this chart, I've averaged over the preceding 10 years to iron out the fluctuations and better show the trend). It's been generally falling since the 1960s excepting a brief period of stability through the 1990s that recent seasons have ignored, the current season in particular during which it's been just 23%.

Next, the red line, which shows the proportion of games in which the team leading at three-quarter time differs from the team leading at half time. This statistic has declined across the period roughly covering the 1980s through to 2000, since which it has stabilised at about 20%.

The navy blue line shows the proportion of games in which the winning team differs from the team leading at three-quarter time. Its trajectory is similar to that of the red line, though it doesn't show the jaunty uptick in recent seasons that the red line does.

Finally, the dotted, light-blue line, which shows the overall proportion of quarters for which the team leading at one break was different from the team leading at the previous break. Its trend has been downwards since the 1960s though the rate of decline has slowed markedly since about 1990.

All told then, if your measure of AFL competitiveness is how often the lead changes from the end of one quarter to the next, you'd have to conclude that AFL games are gradually becoming less competitive.

It'll be interesting to see how the introduction of new teams over the next few seasons affects this measure of competitiveness.

A Competition of Two Halves

/In the previous blog I suggested that, based on winning percentages when facing finalists, the top 8 teams (well, actually the top 7) were of a different class to the other teams in the competition.

Current MARS Ratings provide further evidence for this schism. To put the size of the difference in an historical perspective, I thought it might be instructive to review the MARS Ratings of teams at a similar point in the season for each of the years 1999 to 2010.

(This also provides me an opportunity to showcase one of the capabilities - strip-charts - of a sparklines tool that can be downloaded for free and used with Excel.)

In the chart, each row relates the MARS Ratings that the 16 teams had as at the end of Round 22 in a particular season. Every strip in the chart corresponds to the Rating of a single team, and the relative position of that strip is based on the team's Rating - the further to the right the strip is, the higher the Rating.

The red strip in each row corresponds to a Rating of 1,000, which is always the average team Rating.

While the strips provide a visual guide to the spread of MARS Ratings for a particular season, the data in the columns at right offer another, more quantitative view. The first column is the average Rating of the 8 highest-rated teams, the middle column the average Rating of the 8 lowest-rated teams, and the right column is the difference between the two averages. Larger values in this right column indicate bigger differences in the MARS Ratings of teams rated highest compared to those rated lowest.

(I should note that the 8 highest-rated teams will not always be the 8 finalists, but the differences in the composition of these two sets of eight team don't appear to be material enough to prevent us from talking about them as if they were interchangeable.)

What we see immediately is that the difference in the average Rating of the top and bottom teams this year is the greatest that it's been during the period I've covered. Furthermore, the difference has come about because this year's top 8 has the highest-ever average Rating and this year's bottom 8 has the lowest-ever average Rating.

The season that produced the smallest difference in average Ratings was 1999, which was the year in which 3 teams finished just one game out of the eight and another finished just two games out. That season also produced the all-time lowest rated top 8 and highest rated bottom 8.

While we're on MARS Ratings and adopting an historical perspective (and creating sparklines), here's another chart, this one mapping the ladder and MARS performances of the 16 teams as at the end of the home-and-away seasons of 1999 to 2010.

One feature of this chart that's immediately obvious is the strong relationship between the trajectory of each team's MARS Rating history and its ladder fortunes, which is as it should be if the MARS Ratings mean anything at all.

Other aspects that I find interesting are the long-term decline of the Dons, the emergence of Collingwood, Geelong and St Kilda, and the precipitous rise and fall of the Eagles.

I'll finish this blog with one last chart, this one showing the MARS Ratings of the teams finishing in each of the 16 ladder positions across seasons 1999 to 2010.

As you'd expect - and as we saw in the previous chart on a team-by-team basis - lower ladder positions are generally associated with lower MARS Ratings.

But the "weather" (ie the results for any single year) is different from the "climate" (ie the overall correlation pattern). Put another way, for some teams in some years, ladder position and MARS Rating are measuring something different. Whether either, or neither, is measuring what it purports to -relative team quality - is a judgement I'll leave in the reader's hands.

Is the Home Ground Advantage Disappearing?

/Goalkicking Accuracy Across The Seasons

/Scoring Shots: Not Just Another Statistic

/Using a Ladder to See the Future

/The main role of the competition ladder is to provide a summary of the past. In this blog we'll be assessing what they can tell us about the future. Specifically, we'll be looking at what can be inferred about the make up of the finals by reviewing the competition ladder at different points of the season.

I'll be restricting my analysis to the seasons 1997-2009 (which sounds a bit like a special category for Einstein Factor, I know) as these seasons all had a final 8, twenty-two rounds and were contested by the same 16 teams - not that this last feature is particularly important.

Let's start by asking the question: for each season and on average how many of the teams in the top 8 at a given point in the season go on to play in the finals?

The first row of the table shows how many of the teams that were in the top 8 after the 1st round - that is, of the teams that won their first match of the season - went on to play in September. A chance result would be 4, and in 7 of the 13 seasons the actual number was higher than this. On average, just under 4.5 of the teams that were in the top 8 after 1 round went on to play in the finals.

This average number of teams from the current Top 8 making the final Top 8 grows steadily as we move through the rounds of the first half of the season, crossing 5 after Round 2, and 6 after Round 7. In other words, historically, three-quarters of the finalists have been determined after less than one-third of the season. The 7th team to play in the finals is generally not determined until Round 15, and even after 20 rounds there have still been changes in the finalists in 5 of the 13 seasons.

Last year is notable for the fact that the composition of the final 8 was revealed - not that we knew - at the end of Round 12 and this roster of teams changed only briefly, for Rounds 18 and 19, before solidifying for the rest of the season.

Next we ask a different question: if your team's in ladder position X after Y rounds where, on average, can you expect it to finish.

Regression to the mean is on abundant display in this table with teams in higher ladder positions tending to fall and those in lower positions tending to rise. That aside, one of the interesting features about this table for me is the extent to which teams in 1st at any given point do so much better than teams in 2nd at the same point. After Round 4, for example, the difference is 2.6 ladder positions.

Another phenomenon that caught my eye was the tendency for teams in 8th position to climb the ladder while those in 9th tend to fall, contrary to the overall tendency for regression to the mean already noted.

One final feature that I'll point out is what I'll call the Discouragement Effect (but might, more cynically and possibly accurately, have called it the Priority Pick Effect), which seems to afflict teams that are in last place after Round 5. On average, these teams climb only 2 places during the remainder of the season.

Averages, of course, can be misleading, so rather than looking at the average finishing ladder position, let's look at the proportion of times that a team in ladder position X after Y rounds goes on to make the final 8.

One immediately striking result from this table is the fact that the team that led the competition after 1 round - which will be the team that won with the largest ratio of points for to points against - went on to make the finals in 12 of the 13 seasons.

You can use this table to determine when a team is a lock or is no chance to make the final 8. For example, no team has made the final 8 from last place at the end of Round 5. Also, two teams as lowly ranked as 12th after 13 rounds have gone on to play in the finals, and one team that was ranked 12th after 17 rounds still made the September cut.

If your team is in 1st or 2nd place after 10 rounds you have history on your side for them making the top 8 and if they're higher than 4th after 16 rounds you can sport a similarly warm inner glow.

Lastly, if your aspirations for your team are for a top 4 finish here's the same table but with the percentages in terms of making the Top 4 not the Top 8.

Perhaps the most interesting fact to extract from this table is how unstable the Top 4 is. For example, even as late as the end of Round 21 only 62% of the teams in 4th spot have finished in the Top 4. In 2 of the 13 seasons a Top 4 spot has been grabbed by a team in 6th or 7th at the end of the penultimate round.

Grand Finals: Points Scoring and Margins

/How would you characterise the Grand Finals that you've witnessed? As low-scoring, closely fought games; as high-scoring games with regular blow-out finishes; or as something else?

First let's look at the total points scored in Grand Finals relative to the average points scored per game in the season that immediately preceded them.

Apart from a period spanning about the first 25 years of the competition, during which Grand Finals tended to be lower-scoring affairs than the matches that took place leading up to them, Grand Finals have been about as likely to produce more points than the season average as to produce fewer points.

One way to demonstrate this is to group and summarise the Grand Finals and non-Grand Finals by the decade in which they occurred.

There's no real justification then, it seems, in characterising them as dour affairs.

That said, there have been a number of Grand Finals that failed to produce more than 150 points between the two sides - 49 overall, but only 3 of the last 30. The most recent of these was the 2005 Grand Final in which Sydney's 8.10 (58) was just good enough to trump the Eagles' 7.12 (54). Low-scoring, sure, but the sort of game for which the cliche "modern-day classic" was coined.

To find the lowest-scoring Grand Final of all time you'd need to wander back to 1927 when Collingwood 2.13 (25) out-yawned Richmond 1.7 (13). Collingwood, with efficiency in mind, got all of its goal-scoring out of the way by the main break, kicking 2.6 (20) in the first half. Richmond, instead, left something in the tank, going into the main break at 0.4 (4) before unleashing a devastating but ultimately unsuccessful 1.3 (9) scoring flurry in the second half.

That's 23 scoring shots combined, only 3 of them goals, comprising 12 scoring shots in the first half and 11 in the second. You could see that many in an under 10s soccer game most weekends.

Forty-five years later, in 1972, Carlton and Richmond produced the highest-scoring Grand Final so far. In that game, Carlton 28.9 (177) held off a fast-finishing Richmond 22.18 (150), with Richmond kicking 7.3 (45) to Carlton's 3.0 (18) in the final term.

Just a few weeks earlier these same teams had played out an 8.13 (63) to 8.13 (63) draw in their Semi Final. In the replay Richmond prevailed 15.20 (110) to Carlton's 9.15 (69) meaning that, combined, the two Semi Finals they played generated 22 points fewer than did the Grand Final.

From total points we turn to victory margins.

Here too, again save for a period spanning about the first 35 years of the competition during which GFs tended to be closer fought than the average games that had gone before them, Grand Finals have been about as likely to be won by a margin smaller than the season average as to be won by a greater margin.

Of the 10 most recent Grand Finals, 5 have produced margins smaller than the season average and 5 have produced greater margins.

Perhaps a better view of the history of Grand Final margins is produced by looking at the actual margins rather than the margins relative to the season average. This next table looks at the actual margins of victory in Grand Finals summarised by decade.

One feature of this table is the scarcity of close finishes in Grand Finals of the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s. Only 4 of these Grand Finals have produced a victory margin of less than 3 goals. In fact, 19 of the 29 Grand Finals have been won by 5 goals or more.

An interesting way to put this period of generally one-sided Grand Finals into historical perspective is provided by this, the final graphic for today.

They just don't make close Grand Finals like they used to.

The Differential Difference

/Though there are numerous differences between the various football codes in Australia, two that have always struck me as arbitrary are AFL's awarding of 4 points for a victory and 2 from a draw (why not, say, pi and pi/2 if you just want to be different?) and AFL's use of percentage rather than points differential to separate teams that are level on competition points.

I'd long suspected that this latter choice would only rarely be significant - that is, that a team with a superior percentage would not also enjoy a superior points differential - and thought it time to let the data speak for itself.

Sure enough, a review of the final competition ladders for all 112 seasons, 1897 to 2008, shows that the AFL's choice of tiebreaker has mattered only 8 times and that on only 3 of those occasions (shown in grey below) has it had any bearing on the conduct of the finals.

Historically, Richmond has been the greatest beneficiary of the AFL's choice of tiebreaker, being awarded the higher ladder position on the basis of percentage on 3 occasions when the use of points differential would have meant otherwise. Essendon and St Kilda have suffered most from the use of percentage, being consigned to a lower ladder position on 2 occasions each.

There you go: trivia that even a trivia buff would dismiss as trivial.

The Decline of the Humble Behind

/Last year, you might recall, a spate of deliberately rushed behinds prompted the AFL to review and ultimately change the laws relating to this form of scoring.

Has the change led to a reduction in the number of behinds recorded in each game? The evidence is fairly strong:

So far this season we've seen 22.3 behinds per game, which is 2.6 per game fewer than we saw in 2008 and puts us on track to record the lowest number of average behinds per game since 1915. Back then though goals came as much more of a surprise, so a spectator at an average game in 1915 could expect to witness only 16 goals to go along with the 22 behinds. Happy days.

This year's behind decline continues a trend during which the number of behinds per game has dropped from a high of 27.3 per game in 1991 to its current level, a full 5 behinds fewer, interrupted only by occasional upticks such as the 25.1 behinds per game recorded in 2007 and the 24.9 recorded in 2008.

While behind numbers have been falling recently, goals per game have also trended down - from 29.6 in 1991, to this season's current average of 26.8. Still, AFL followers can expect to witness more goals than behinds in most games they watch. This wasn't always the case. Not until the season of 1969 had there been a single season with more goals than behinds, and not until 1976 did such an outcome became a regular occurrence. In only one season since then, 1981, have fans endured more behinds than goals across the entire season.

On a game-by-game basis, 90 of 128 games this season, or a smidge over 70%, have produced more goals than behinds. Four more games have produced an equal number of each.

As a logical consequence of all these trends, behinds have had a significantly smaller impact on the result of games, as evidenced by the chart below which shows the percentage of scoring attributable to behinds falling from above 20% in the very early seasons to around 15% across the period 1930 to 1980, to this season's 12.2%, the second-lowest percentage of all time, surpassed only by the 11.9% of season 2000.

(There are more statistical analyses of the AFL on MAFL Online's sister site at MAFL Stats.)

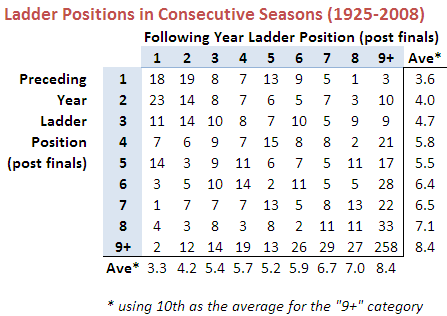

From One Year To The Next: Part 2

/Last blog I promised that I'd take another look at teams' year-to-year changes in ladder position, this time taking a longer historical perspective.

For this purpose I've elected to use the period 1925 to 2008 as there have always been at least 10 teams in the competition from that point onwards. Once again in this analysis I've used each team's final ladder position, not their ladder position as at the end of the home and away season. Where a team has left or joined the competition in a particular season, I've omitted its result for the season in which it came (since there's no previous season) or went (since there's no next season).

As the number of teams making the finals has varied across the period we're considering, I'll not be drawing any conclusions about the rates of teams making or missing the finals. I will, however, be commenting on Grand Final participation as each season since 1925 has culminated in such an event.

Here's the raw data:

(Note that I've grouped all ladder positions of 9th or lower in the "9+" category. In some years this incorporates just two ladder positions, in others as many as eight.)

A few things are of note in this table:

- Losing Grand Finalists are more likely than winning Grand Finalists to win in the next season.

- Only 10 of 83 winning Grand Finalists finished 6th or lower in the previous season.

- Only 9 of 83 winning Grand Finalists have finished 7th or lower in the subsequent season.

- The average ladder position of a team next season is highly correlated with its position in the previous season. One notable exception to this tendency is for teams finishing 4th. Over one quarter of such teams have finished 9th or worse in the subsequent season, which drags their average ladder position in the subsequent year to 5.8, below that of teams finishing 5th.

- Only 2 teams have come from 9th or worse to win the subsequent flag - Adelaide, who won in 1997 after finishing 12th in 1996; and Geelong, who won in 2007 after finishing 10th in 2006.

- Teams that finish 5th have a 14-3 record in Grand Finals that they've made in the following season. In percentage terms this is the best record for any ladder position.

Here's the same data converted into row percentages.

Looking at the data in this way makes a few other features a little more prominent:

- Winning Grand Finalists have about a 45% probability of making the Grand Final in the subsequent season and a little under a 50% chance of winning it if they do.

- Losing Grand Finalists also have about a 45% probability of making the Grand Final in the subsequent season, but they have a better than 60% record of winning when they do.

- Teams that finish 3rd have about a 30% chance of making the Grand Final in the subsequent year. They're most likely to be losing Grand Finalists in the next season.

- Teams that finish 4th have about a 16% chance of making the Grand Final in the subsequent year. They're most likely to finish 5th or below 8th. Only about 1 in 4 improve their ladder position in the ensuing season.

- Teams that finish 5th have about a 20% chance of making the Grand Final in the subsequent year. These teams tend to the extremes: about 1 in 6 win the flag and 1 in 5 drops to 9th or worse. Overall, there's a slight tendency for these teams to drop down the ladder.

- Teams that finish 6th or 7th have about a 20% chance of making the Grand Final in the subsequent year. Teams finishing 6th tend to drop down the ladder in the next season; teams finishing 7th tend to climb.

- Teams that finish 8th have about a 8.5% chance of making the Grand Final in the subsequent year. These teams tend to climb in the ensuing season.

- Teams that finish 9th or worse have about a 3.5% chance of making the Grand Final in the subsequent year. They also have a roughly 2 in 3 chance of finishing 9th or worse again.

So, I suppose, relatively good news for Cats fans and perhaps surprisingly bad news for St Kilda fans. Still, they're only statistics.

From One Year To The Next: Part 1

/With Carlton and Essendon currently sitting in the top 8, I got to wondering about the history of teams missing the finals in one year and then making it the next. For this first analysis it made sense to choose the period 1997 to 2008 as this is the time during which we've had the same 16 teams as we do now.

For that period, as it turns out, the chances are about 1 in 3 that a team finishing 9th or worse in one year will make the finals in the subsequent year. Generally, as you'd expect, the chances improve the higher up the ladder that the team finished in the preceding season, with teams finishing 11th or higher having about a 50% chance of making the finals in the subsequent year.

Here's the data I've been using for the analysis so far:

And here's that same data converted into row percentages and grouping the Following Year ladder positions.

Note that in these tables I've used each team's final ladder position, not their ladder position as at the end of the home and away season. So, for example, Geelong's 2008 ladder position would be 2nd, not 1st.

Teams that make the finals in a given year have about a 2 in 3 chance of making the finals in the following year. Again, this probability tends to increase with higher ladder position: teams finishing in the top 4 places have a better than 3 in 4 record for making the subsequent year's finals.

One of the startling features of these tables is just how much better flag winners perform in subsequent years than do teams from any other position. In the first table, under the column headed "Ave" I've shown the average next-season finishing position of teams finishing in any given position. So, for example, teams that win the flag, on average, finish in position 3.5 on the subsequent year's ladder. This average is bolstered by the fact that 3 of the 11 (or 27%) premiers have gone back-to-back and 4 more (another 36%) have been losing Grand Finalists. Almost 75% have finished in the top 4 in the subsequent season.

Dropping down one row we find that the losing Grand Finalist from one season fares much worse in the next season. Their average ladder position is 6.6, which is over 3 ladder spots lower than the average for the winning Grand Finalist. Indeed, 4 of the teams that finished 2nd in one season missed the finals in the subsequent year. This is true of only 1 winning Grand Finalist.

In fact, the losing Grand Finalists don't tend to fare any better than the losing Preliminary Finalists, who average positions 6.0 (3rd) and 6.8 (4th).

The next natural grouping of teams based on average ladder position in the subsequent year seems to be those finishing 5th through 11th. Within this group the outliers are teams finishing 6th (who've tended to drop 3.5 places in the next season) and teams finishing 9th (who've tended to climb 1.5 places).

The final natural grouping includes the remaining positions 12th through 16th. Note that, despite the lowly average next-year ladder positions for these teams, almost 15% have made the top 4 in the subsequent year.

A few points of interest on the first table before I finish:

- Only one team that's finished below 6th in one year has won the flag in the next season: Geelong, who finished 10th in 2006 and then won the flag in 2007

- The largest season-to-season decline for a premier is Adelaide's fall from the 1998 flag to 13th spot in 1999.

- The largest ladder climb to make a Grand Final is Melbourne's rise from 14th in 1999 to become losing Grand Finalists to Essendon in 2000.

Next time we'll look at a longer period of history.

Limning the Ladder

/It's time to consider the grand sweep of football history once again.

This time I'm looking at the teams' finishing positions, in particular the number and proportion of times that they've each finished as Premiers, Wooden Spooners, Grand Finalists and Finalists, or that they've finished in the Top Quarter or Top Half of the draw.

Here's a table providing the All-Time data.

Note that the percentage columns are all as a percentage of opportunities. So, for a season to be included in the denominator for a team's percentage, that team needs to have played in that season and, in the case of the Grand Finalists and Finalists statistics, there needs to have been a Grand Final (which there wasn't in 1897 or 1924) or there needs to have been Finals (which, effectively, there weren't in 1898, 1899 or 1900).

Looking firstly at Premierships, in pure number terms Essendon and Carlton tie for the lead on 16, but Essendon missed the 1916 and 1917 seasons and so have the outright lead in terms of percentage. A Premiership for West Coast in any of the next 5 seasons (and none for the Dons) would see them overtake Essendon on this measure.

Moving then to Spoons, St Kilda's title of the Team Most Spooned looks safe for at least another half century as they sit 13 clear of the field, and University will surely never relinquish the less euphonius but at least equally as impressive title of the Team With the Greatest Percentage of Spooned Seasons. Adelaide, Port Adelaide and West Coast are the only teams yet to register a Spoon (once the Roos' record is merged with North Melbourne's).

Turning next to Grand Finals we find that Collingwood have participated in a remarkable 39 of them, which equates to a better than one season in three record and is almost 10 percentage points better than any other team. West Coast, in just 22 seasons, have played in as many Grand Finals as have St Kilda, though St Kilda have had an additional 81 opportunities.

The Pies also lead in terms of the number of seasons in which they've participated in the Finals, though West Coast heads them in terms of percentages for this same statistic, having missed the Finals less than one season in four across the span of their existence.

Finally, looking at finishing in the Top Half or Top Quarter of the draw we find the Pies leading on both of these measures in terms of number of seasons but finishing runner-up to the Eagles in terms of percentages.

The picture is quite different if we look just at the 1980 to 2008 period, the numbers for which appear below.

Hawthorn now dominates the Premiership, Grand Finalist and finishing in the Top Quarter statistics. St Kilda still own the Spoon market and the Dons lead in terms of being a Finalist most often and finishing in the Top Half of the draw most often.

West Coast is the team with the highest percentage of Finals appearances and highest percentage of times finishing in the Top Half of the draw.

Percentage of Points Scored in a Game

/We statisticians spend a lot of our lives dealing with the bell-shaped statistical distribution known as the Normal or Gaussian distribution. It describes a variety of phenomena in areas as diverse as physics, biology, psychology and economics and is quite frankly the 'go-to' distribution for many statistical purposes.

So, it's nice to finally find a footy phenomenon that looks Normally distributed.

The statistic is the percentage of points scored by each team is a game and the distribution of this statistic is shown for the periods 1897 to 2008 and 1980 to 2008 in the diagram below.

Both distributions follow a Normal distribution quite well except in two regards:

- They fall off to zero in the "tails" faster than they should. In other words, there are fewer games with extreme results such as Team A scoring 95% of the points and Team B only 5% than would be the case if the distribution were strictly normal.

- There's a "spike" around 50% (ie for very close and drawn games) suggesting that, when games are close, the respective teams play in such a way as to preserve the narrowness of the margin - protecting a lead rather than trying to score more points when narrowly in front and going all out for points when narrowly behind.

Knowledge of this fact is unlikely to make you wealthy but it does tell us that we should expect approximately:

- About 1 game in 3 to finish with one team scoring about 55% or more of the points in the game

- About 1 game in 4 to finish with one team scoring about 58% or more of the points in the game

- About 1 game in 10 to finish with one team scoring about 65% or more of the points in the game

- About 1 game in 20 to finish with one team scoring about 70% or more of the points in the game

- About 1 game in 100 to finish with one team scoring about 78% or more of the points in the game

- About 1 game in 1,000 to finish with one team scoring about 90% or more of the points in the game

The most recent occurrence of a team scoring about 90% of the points in a game was back in Round 15 of 1989 when Essendon 25.10 (160) defeated West Coast 1.12 (18).

We're overdue for another game with this sort of lopsided result.

Teams' Performances Revisited

/In a comment on the previous posting, Mitch asked if we could take a look at each team's performance by era, his interest sparked by the strong all-time performance of the Blues and his recollection of their less than stellar recent seasons.

Here's the data:

So, as you can see, Carlton's performance in the most recent epoch is significantly below its all-time performance. In fact, the 1993-2008 epoch is the only one in which the Blues failed to return a better than 50% performance.

Collingwood, the only team with a better lifetime record than Carlton, have also had a well below par last epoch during which they too have registered their first sub-50% performance, continuing a downward trend which started back in Epoch 2.

Six current teams have performed significantly better in the 1993-2008 epoch than their all-time performance: Geelong (who registered their best ever epoch), Sydney (who cracked 50% for the first time in four epochs), Brisbane (who could hardly but improve), the Western Bulldogs (who are still yet to break 50% for an epoch, their 1945-1960 figure being actually 49.5%), North Melbourne (who also registered their best ever epoch), and St Kilda (who still didn't manage 50% for the epoch, a feat they've achieved only once).

Just before we wind up I should note that the 0% for University in Epoch 2 is not an error. It's the consequence of two 0 and 18 performances by Uni in 1913 and 1914 which, given that these followed directly after successive 1 and 17 performances in 1911 and 1912, unsurprisingly heralded the club's demise. Given that Uni's sole triumph of 1912 came in the third round, by my calculations that means University lost its final 51 matches.