All You Ever Wanted to Know About Favourite-Longshot Bias ...

/Previously, on at least a few occasions, I've looked at the topic of the Favourite-Longshot Bias and whether or not it exists in the TAB Sportsbet wagering markets for AFL.

A Favourite-Longshot Bias (FLB) is said to exist when favourites win at a rate in excess of their price-implied probability and longshots win at a rate less than their price-implied probability. So if, for example, teams priced at $10 - ignoring the vig for now - win at a rate of just 1 time in 15, this would be evidence for a bias against longshots. In addition, if teams priced at $1.10 won, say, 99% of the time, this would be evidence for a bias towards favourites.

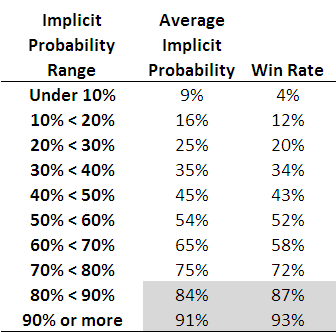

When I've considered this topic in the past I've generally produced tables such as the following, which are highly suggestive of the existence of such an FLB.

Each row of this table, which is based on all games from 2006 to the present, corresponds to the results for teams with price-implied probabilities in a given range. The first row, for example, is for all those teams whose price-implied probability was less than 10%. This equates, roughly, to teams priced at $9.50 or more. The average implied probability for these teams has been 9%, yet they've won at a rate of only 4%, less than one-half of their 'expected' rate of victory.

As you move down the table you need to arrive at the second-last row before you come to one where the win rate exceed the expected rate (ie the average implied probability). That's fairly compelling evidence for an FLB.

This empirical analysis is interesting as far as it goes, but we need a more rigorous statistical approach if we're to take it much further. And heck, one of the things I do for a living is build statistical models, so you'd think that by now I might have thrown such a model at the topic ...

A bit of poking around on the net uncovered this paper which proposes an eminently suitable modelling approach, using what are called conditional logit models.

In this formulation we seek to explain a team's winning rate purely as a function of (the natural log of) its price-implied probability. There's only one parameter to fit in such a model and its value tells us whether or not there's evidence for an FLB: if it's greater than 1 then there is evidence for an FLB, and the larger it is the more pronounced is the bias.

When we fit this model to the data for the period 2006 to 2010 the fitted value of the parameter is 1.06, which provides evidence for a moderate level of FLB. The following table gives you some idea of the size and nature of the bias.

The first row applies to those teams whose price-implied probability of victory is 10%. A fair-value price for such teams would be $10 but, with a 6% vig applied, these teams would carry a market price of around $9.40. The modelled win rate for these teams is just 9%, which is slightly less than their implied probability. So, even if you were able to bet on these teams at their fair-value price of $10, you'd lose money in the long run. Because, instead, you can only bet on them at $9.40 or thereabouts, in reality you lose even more - about 16c in the dollar, as the last column shows.

We need to move all the way down to the row for teams with 60% implied probabilities before we reach a row where the modelled win rate exceeds the implied probability. The excess is not, regrettably, enough to overcome the vig, which is why the rightmost entry for this row is also negative - as, indeed, it is for every other row underneath the 60% row.

Conclusion: there has been an FLB on the TAB Sportsbet market for AFL across the period 2006-2010, but it hasn't been generally exploitable (at least to level-stake wagering).

The modelling approach I've adopted also allows us to consider subsets of the data to see if there's any evidence for an FLB in those subsets.

I've looked firstly at the evidence for FLB considering just one season at a time, then considering only particular rounds across the five seasons.

So, there is evidence for an FLB for every season except 2007. For that season there's evidence of a reverse FLB, which means that longshots won more often than they were expected to and favourites won less often. In fact, in that season, the modelled success rate of teams with implied probabilities of 20% or less was sufficiently high to overcome the vig and make wagering on them a profitable strategy.

That year aside, 2010 has been the year with the smallest FLB. One way to interpret this is as evidence for an increasing level of sophistication in the TAB Sportsbet wagering market, from punters or the bookie, or both. Let's hope not.

Turning next to a consideration of portions of the season, we can see that there's tended to be a very mild reverse FLB through rounds 1 to 6, a mild to strong FLB across rounds 7 to 16, a mild reverse FLB for the last 6 rounds of the season and a huge FLB in the finals. There's a reminder in that for all punters: longshots rarely win finals.

Lastly, I considered a few more subsets, and found:

- No evidence of an FLB in games that are interstate clashes (fitted parameter = 0.994)

- Mild evidence of an FLB in games that are not interstate clashes (fitted parameter = 1.03)

- Mild to moderate evidence of an FLB in games where there is a home team (fitted parameter = 1.07)

- Mild to moderate evidence of a reverse FLB in games where there is no home team (fitted parameter = 0.945)

FLB: done.

Is There a Favourite-Longshot Bias in AFL Wagering?

/The other night I was chatting with a few MAFL Investors and the topic of the Favourite-Longshot bias - and whether or not it exists in TAB AFL betting - came up. Such a bias is said to exist if punters tend to do better wagering on favourites than they do wagering on longshots.

The bias has been found in a number of wagering markets, among them Major League Baseball, horse racing in the US and the UK, and even greyhound racing. In its most extreme form, so mispriced do favourites tend to be that punters can actually make money over the long haul by wagering on them. I suspect that what prevents most punters from exploiting this situation - if they're aware of it - is the glacial rate at which profits accrue unless large amounts are wagered. Wagering $1,000 on a contest with the prospect of losing it all in the event of an upset or, instead, of winning just $100 if the contest finishes as expected seems, for most punters, like a lousy way to spend a Sunday afternoon.

Anyway, I thought I'd analyse the data that I've collected over the previous 3 seasons to see if I can find any evidence of the bias. The analysis is summarised in the table below.

Clearly such a bias does exist based on my data and on my analysis, in which I've treated teams priced at $1.90 or less as favourites and those priced at $5.01 or more as longshots. Regrettably, the bias is not so pronounced that level-stake wagering on favourites becomes profitable, but it is sufficient to make such wagering far less unprofitable than wagering on longshots.

In fact, wagering on favourites - and narrow underdogs too - would be profitable but for the bookie's margin that's built into team prices, which we can see has averaged 7.65% across the last three seasons. Adjusting for that, assuming that the 7.65% margin is applied to favourites and underdogs in equal measure, wagering on teams priced under $2.50 would produce a profit of around 1-1.5%.

In the table above I've had to make some fairly arbitrary decisions about the price ranges to use, which inevitably smooths out some of the bumps that exist in the returns for certain, narrower price ranges. For example, level-stake wagering on teams priced in the range $3.41 to $3.75 would have been profitable over the last three years. Had you the prescience to follow this strategy you'd have made 32 bets and netted a profit of 9 units, which is just over 28%.

A more active though less profitable strategy would have been to level-stake wager on all teams priced in the $2.41 to $3.20 price range, which would have led you to make 148 wagers and pocket a 3.2 unit or 2.2% profit.

Alternatively, had you hired a less well-credentialled clairvoyant and as a consequence instead level-stake wagered on all the teams priced in the $1.81 to $2.30 range - a strategy that suffers in part from requiring you to bet on both teams in some games and so guarantee a loss - you'd have made 222 bets and lost 29.6 units, which is a little over a 13% loss.

Regardless, if there is a Favourite-Longshot bias, what does it mean for MAFL?

In practical terms all it means is that a strategy of wagering on every longshot would be painfully unprofitable, as last year's Heritage Fund Investors can attest. That’s not to say that there's never value in underdog wagering, just that there isn’t consistent value in doing so. What MAFL aims to do is detect and exploit any value – whether it resides in favourites or in longshots.

What MAFL also seeks to do is match the size of its bet to the magnitude of its assessed advantage. That, though, is a topic for another day.