The Chase UK: Predicting the High and Low Offers During the Course of an Episode - An Update

/In an earlier blog, we built models to predict the Low and High Offers made to contestants in The Chase UK and found that we were able to explain roughly half the variability in the Offers made - a little more in the case of models built for the Low Offers by Seat, and generally a little less in the case of models build for the High Offers by Seat.

Since that blog was posted, I’ve had some excellent suggestions for things to try that might improve the models’ fit, and I’ve also had some thoughts of my own.

NEW VARIABLES

One of the findings from the earlier modelling was that The Chase UK’s most-recent new Chaser, Darragh, makes, on average, higher offers than other Chasers. That got me to wondering if there might be a time dimension to the offers such that offers made in different seasons might be systematically different from one another.

So, as one new variable, we’ll include Season as a categorical variable, with values from “1” to “15”.

I also recalled performing some earlier analyses on the The Chase Australia data where I looked at the possible effects of gender on the behaviour and success of teams. In the context of the current analysis, that had me thinking about the possibility that different offers are made to players in similar situations who differ only in the gender associated with their names.

So, I also decided to include a variable reflecting the likelihood that the contestant’s name was male or female, which I created using the Namsor service. It allowed me to attach a value between 0 and 1 to each contestant name on the basis of how likely Namsor had determined that name to be male gendered.

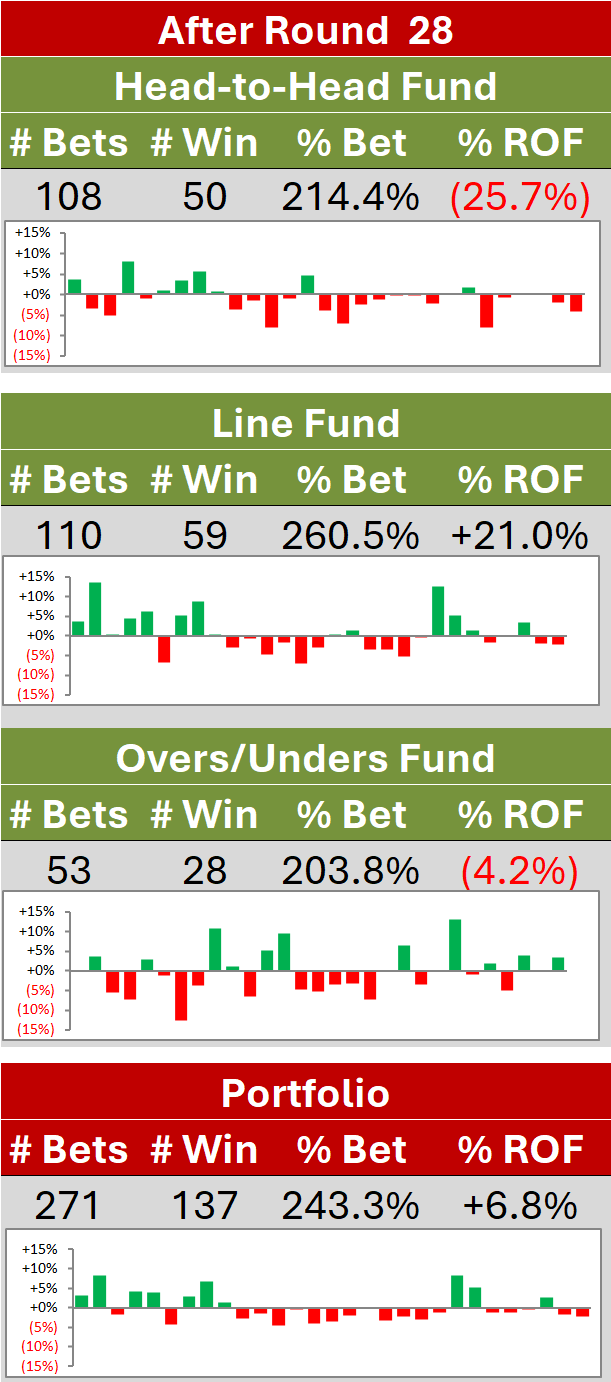

The results of including these two new variables are shown in the table below. They appear on the righthand side of the table, with the results from the previous analysis appearing on the left.

The highlights of the new analysis are as follows:

The new variables, together, help explain as much as an additional 10% of the variability in offers, in some cases

Most of that additional explanatory power comes from adding the Season variable, which is (jointly) statistically significant in all eight models

The coefficients for the Season variable suggest that

the Low Offers for Seat 1 have progressively got lower, on average, since the early seasons

the Low Offers for Seats 2 and 3 dropped, on average, in Season 2, and have remained at roughly the same level since

the Low Offers for Seat 4 have progressively got much lower, on average, since the early seasons

the High Offers for all Seats have, on average, got much higher from season to season, but especially so for Seats 1 and 4

These increases over time in the High Offers explains some of the tendency to associate Darragh, who’s only participated in recent seasons, with higher offers compared to other Chasers. However, even once we adjust for recent season offer increases, Darragh is still making higher-than-average offers (as evidenced by the row of numbers alongside his name on the righthand side of the table above)

Notwithstanding this, the coefficients on the Chasers are, jointly, not statistically significantly different from zero at the 10% level in four of the eight models, which makes me wonder if the Chasers themselves have relatively little control over the offers they make, and most of what we’re seeing in the numbers against the Chasers is noise

With a few exceptions, the coefficients on the variables that are common to both the old and the new models end up being identical in sign and quite similar in magnitude, suggesting that the new variables are predominantly explaining independent sources of variability

The variable related to contestants’ name-gender suggests that this aspect has relatively little affect on the size of offers made, with one very notable exception: male-gendered names from Seat 4 tend to receive statistically significantly lower High Offers - as much as £2,000 lower for strongly male-gendered names such as Ian, Bradly, or Paul (according to Namsor)

BASIC STATISTICS

To give you some idea about the range and variability of the variables in the model, I’ve put together the table below, which provides, by Seat, the 10th, 50th (median) and 90th percentile for each variable.

One interesting observation from this table is that male-gendered names are more likely to be in Seat 1, and female-gendered names in Seat 3, whereas Seats 2 and 4 are about equally as likely to have a male-gendered as a female-gendered name.

OTHER SUGGESTIONS

I received a couple of other good suggestions for things to try, one of which was to fit the log of High Offers rather than High Offers itself on the basis that this would reduce the variability in the thing we’re trying to fit. It turns out that this does allow us to explain a numerically larger proportion of the variability in the our target variables - log(High Offers) here - but, if we transform the model predictions back into those for High Offers, we do not much better, and sometimes no better, than simply fitting High Offers to begin with.

Another thought was to explore the recent performance of each Chaser to see if that might affect his or her offer- making. To test this I looked at Chasers’ win percentage over the last 10 episodes in which they appeared. This variable did not turn out to be statistically significant, which I think lends weight to my hypothesis that the Chasers themselves have relatively little to do with the offers that are made.

Thank you to those who have read the earlier blog and made comment or just offered encouragement. I remain open to further suggestions about variables to try.